A clarification of "demand" based errors

Hector McNeill1

SEEL

This article is a sequel to the short article entitled, "A clarification of supply side economics" and the article "Resources, economic capacity, endogenous & exogenous means of exchange". In the first article, for the sake of brevity, I only set out the position of Jean Baptiste Say as well as that of the real incomes approach. In the second article I explore the destructive role of exogenous money in "demand management". These explanations are fairly straightforward and should alarm most as to why many economists and governments pursue alternative destructive aggregate demand management policies to the detriment of the majority. This article looks at the fallacies and established dangers of monetary policies which are a major element in "demand led" economic policies. I will cover so-called Modern Monetary Theory and Keynesianism in subsequent articles.

|

The policy instruments

Our main experience with the monetary policies have boiled down to the application of just two instruments:

- Variations in money volumes

- Variations in interest rates

|

Although previously, the nature of manipulations in money volumes was always unclear, it has always been based on the government raising debt from private banks and the variations in private sector money volumes is based on banks issuing loans. The fact that increases in money volumes arise from bank issuance of debt was explained in a Bank of England brief in 2014: "Money creation in the modern economy". So variations in money volumes is simply variations in the extent of debt of the economy to private banks.

Variations in interest rates do not arise from a free market or natural interest rates (see, "Is there such a thing as a natural interest rate? - note") but rather from a centrally imposed base rate with banks adding around 6% as their lowest operational interest rates. Therefore the imposition of interest rates is simply a lever to establish the baseline levels of interest rates applied in bank lending into the economy. Although presented as a macroeconomic demand management this form of monetary policy is more about the degree to which bank turnover participates in the economy. This might appear to be an assertion emanating from a philosophical position on the role of banks; it is not. It is based on the simple analysis of how this system operates and its impact on productivity and real incomes or purchasing power of constituents. Why this form of monetary policy does not workThe theoretical foundations of monetary policy are summed up on a model known as the quantity theory of money (QTM). The QTM has been around for centuries and variously justified as the explanation for inflation. The irrelevance of this model arises from the fact that it is not a determinant model because key determinants are missing. However, it is always instructive to observe leading monetarists answering the question as to what it the actual process that causes a rise in money volume to end up as inflation. Their "explanations" are always completely unconvincing. In the 1970s I recall having my attention drawn to this fact by the difficulty Milton Friedman had in explaining the process. He could not do so. The best he could come up with was, " this happens over the long term"; hardly a serious explanation of the process.  However, by 1976 the research giving rise to the real incomes approach had established that inflation is not caused by "money volumes". In fact there is no direct functional relationship. Inflation is measured as the average of all of the rises in unit prices each associated with the pricing decisions of individual economic units. Pricing decisions determine the price performance ratio (PPR) (see, "The Price Performance Ratio") of companies where the PPR is the percentage change in unit output prices in response to changes in unit input costs. If the PPR exceeds unity (>1.00) and costs are rising, then inflation will be increased. If the PPR is equal to unity (1.00) inflation will continue at the input rate. If the PPR is less than unity (<1.00), inflation will be reduced. None of these states has any relationship to "money volumes". This fact has been discussed at length in several articles on this site, the latest being a recently updated article entitled, "What are the elements of a supply side policy? - Part 1" under the sub-heading "What causes inflation". A Real Theory of Money (RTM)I have produced a paper which proposes replacing the conventional quantity theory of money equation which cannot explain the outcome of quantitative easing (QE) with one based on what is known as the Cambridge equation that I have adjusted to explain the prejudice created by QE in real income terms. This paper can be viewed or downloaded by clicking on the image on the right.

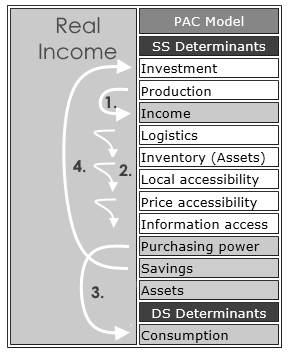

The Production, Accessibility & Consumption Model

Note that the all of the Demand Side Determinants (DS Determinants) generating consumption, come from the Supply Side Determinants side. |

|

|

Interest rates and inflation

If money volumes have no connection to inflation, interest rates as imposed by dictat, have an even less convincing contribution in controlling inflation. Where inflation is caused by companies contributing to input inflation by increasing the rate (PPR >1.00) a basic cause of this decision can be the desire of a decision maker to compound future prices and revenues so as to maintain their real revenue by attempting to overcome the devaluation of the currency caused by inflation. However, this is counterproductive since this becomes a generalized behaviour which can career towards hyperinflation. This has been observed in many countries and especially Brazil in the late 1970s. The preferable decision by a manager is to seek ways to increase productivity so as to facilitate the absorption of input inflation so as to remain price competitive and to compensate for devaluation of revenues as a result of inflation, by becoming more competitive, selling more and in this way improve the corporate real income status. However, this requires investment and sometimes raising a loan.

The paradox of centrally imposed interest rates under aggregate demand management and "guided" by the flawed QTM mistakenly increases interest rates to counter inflation. This is exactly the opposite of what is required. Raising interest rates is a direct disincentive to raising loans exactly when they are needed to take action to improve productivity and competitivity and to moderate or even reduce output prices. It should be added that the use of finance in the form of loans is in any case inflationary because of the added interest raises the actual investment outlays required. Where interest rates have been at a level to have encouraged savings, then these can provide a more productive and less inflationary solution for productivity investment. Invariably the short to medium term impacts of increased interest rates is to increase inflation and real income erosion and this is invariably associated with increases in unemployment that are directly attributable to the interest rate rises. The payment of mortgages for lower income groups can become unsustainable and as a result home repossessions can result as a direct result of this policy imposition.

Interest rates and deflation

Where prices, for various reasons stabilize and inflation falls below 2% there is a reaction within the policy makers who operate on the basis of the Aggregate Demand Model and the flawed QTM, to lower interest rates and attempt to infuse more funds into the economy through lower interest debt. Quantitative easing (QE) is an example of this approach and the outcome has been a diversion of "cheap money" by the financial intermediaries and banks to the purchase of assets including land, real estate, precious metals, rare art objects and shares acquired through buy backs. This results in the volume of money within the supply side production economy drying up and as a result little ability to invest in higher productivity technologies and techniques and to pay workers higher wages so as to raise disposable incomes and therefore consumption. Because interest rates are close to zero this policy destroys savings as an alternative endogenous source of investment finance and causes a displacement of the right of individuals and companies to save by an imposition of policy that result in exogenous funds from banks being the only source of investment finance.

This explains how the exogenous funds that were not generated by the supply side, bank loans, have intruded so as to deny the supply side of funds for investment while channeling these exogenous funds into assets that would have normally remained within the purchasing power of the supply side. However rather than see economic growth, in spite of close to zero interest rates, this has resulted in lower real incomes, lower substantive investment and deficient growth in productivity. As is self-evident, the rise in exogenous money did not have any practical impact on "aggregate demand" or, in reality, inflation.

Without this intervention, incentives applied to the logistics elements of accessibility to products, information and unit prices could facilitate a real incomes policy making use of the price performance ratio and price performance levy so as to guide investment towards higher productivity. By having endogenous supply side money cash flow and savings available to invest could achieve real growth in real consumption. This points to a the basics of a Real Aggregate Growth Model (RAGM). As explained in the paper referred to, "A Real Theory of Money", the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) is alarmingly over-simplistic and does not represent a serious decision analysis model, certainly not one that should have ever been used as a basis for justifying decisions that have undermined wellbeing by creating the degrees of havoc experienced in the lives of constituents. The more correct Real Theory of Money (RTM) makes the degree of destruction of policy impositions based on exogenous finance easier to trace. It is noteworthy that both the QTM and RTM provide no functional means of relating "money volumes" to inflation. Inflation was and remains the outcome of the collectives outcome of individual microeconomic endogenous pricing decisions by companies and individuals that are unrelated to exogenously generated "money volumes".

1 Hector McNeill is the Director of SEEL-Systems Engineering Economics Lab.

|

|

|

|