Sense and nonsense on interest rates

Hector McNeill1

SEEL

As a result of a prolonged attempt to manage "recovery" through quantitative easing, policy-makers have lost control over the ability to influence demand through centrally-imposed interest rates. Debt on the part of governments, companies and consumers now exceeds the pre-crisis conditions of 2007. The grey market in derivatives and unbacked securities, which lies beyond the grasp of macroeconomic policy control, exceeds the GNP several times.

Recently, some of the managers of the largest pension funds have realised that the options between equity and fixed income savings have virtually disappeared and all returns are low in real terms; indeed some holdings have turned into negative yields. At the moment, the instability in markets under the international tensions tied to sanctions and "trade policies", in addition to this inept monetary policy are likely to tip the world economy into a period of slumpflation, inflation and rising unemployment. We went through this scenario in 1970s-1980s but without facing such chronic debt levels, and yet the combination of supply side economics and monetary policy using interest rates offered no effective solutions. We also witnessed the impact of excessive debt in 2008 to 2019 and again, the new variant of monetary policy has failed to stem the risks to the world economy. To be blunt, the setting of interest rates, the only tool left in the monetary policy toolbox can be seen to have been a mirage; it has not been effective it has only sustained a considerable deepening policy-imposed prejudice.

This article explains why the former objectives of interest rates have evaporated in an uncontrolled growth in financialization which started in the 1970s and which has extended its full negative impact on the real economy. |

The outcome of various attempts at quantitative easing (reduction in interst rates and issuance of increasing amounts of debt) was supposed to be a solution for banks to "recover their balance sheets" following the 2008 financial crisis. Today, central banks, who have been arranging things very much in favour of the banks are now afraid to raise interest rates because the massive overhang of debt could be converted into another crash as debtors become incapable of paying their premiums - a generalised sub-prime-equivalent crisis. So the central banks have backed the economies into a corner from which it is difficult to escape. The problem is that with a bad precedent of the 2008 bank bail out, politicians might see no other alternative other than to attempt to bail the banks out again. On the other hand many banks have not sorted out their balance sheets and the state of affairs with respect to unsecured debt and assets is worse than in 2007. If the central banks and their main constituents, the banks, have their way, they will have no compunction other than to demand such "support" on the grounds they are too significant to the economy to fail while the rest of the economy pays a heavy price for the bank's and the central bank's failures in judgement.

Failures in judgement?Decisions based on judgement of circumstances for the banks have become increasingly focused on the interests of bank shareholders. The more balanced business objectives between services of significance to macroeconomic policy and shareholder interests has given way to a shareholder value focus as can be seen from the displacement of money from the consumer and business transactional money streams to asset holding and trading ( see

The outcome of quantitative easing on real incomes - summary note ) and the impacts have been disastrous (see

The occlusion of lower middle and lower income family purchasing power under quantitative easing - summary note ).

In terms of constitutional economics there needs to a reintroduction of a monitored and moderated trade-off between corporate and national macroeconomic interests in all decisions. Since the 1970s roughly coinciding with Nixon's removal of the US dollar from the Gold Standard, financialization has come to dominate economic thinking and policy ( see

The journey from 1971 to 2014 - the consolidation of financialization ). The financial regulatory agencies became more and more biased towards the interests of the banks reflected in the introduction of increasingly "light touch" regulations and altogether absurdly insignificant penalities for serious transgressions. Thus governments have created a financial legal and regulatory framework where the need to trade-off the implications of the law, prudence and ethics has been killed off. In the past regulatory penalties (law) combined with a public role of supporting the general interests of the constituency (nation) meant that prudent decisions took on a transparently ethical character. However, now that the tiny penalties associated with quite serious bank infractions are no more than a minor cost to doing business, what constitute prudent decisions are increasingly those that only favour bank shareholder interests with no serious consideration of the general interests of the constituents (the nation). Ethical decision-making, the alignment of decisions with the requirement and spirit of of contituent interests and legislation, is dead. The responsibility for this lies with government legislation and politicians whose decision-making on financial regulation has been unethical in favouring banks and ignoring the interests of voters. This ability to ignor constituent interests is a primary form of corruption in procedures which results in there being no transparent inputs of constituency interests and even if expressions of concern are articulated, no significant weight is assigned to them; they are effectively ignored. Although this analysis explains why banks do what they do, it is not an excuse for what has become unscrupulous and socially-damaging behaviour.

Failed strategy and dubious efficiencyBy driving interest rates down, quatitative easing (QE), has obliterated returns on savings impacting a community made up of large investment funds and pensioners and others depending on fixed income from interest on savings. Governments did not consult as to the interests of this community before taking such policy action; there was no serious analysis of the likely impact on them before imposing QE. From the banks' perspective this move was a perfect strategy to eliminate the competition that comes from private saving, part of the thinking was that this could also destroy mutual savings groups such as building societies that provide mortgages for domestic housing. In the end this would mean that the only source for money for economic growth would not come from saving but from banks meaning more future business based on debt. Certainly previous ill-judged financial legislation had attempted to undermine building societies by "allowing" them to become banks. Some building society executives took advanatge if this new legislation to enrich themselves and some members. The most proactive in the UK was Northen Rock in the North East which attempted to expand by substituting personal savings by raising capital on the international money markets.

The arrogance of Norhern Rock executives explaining their model to a select committee in Parliament asserted that building societies were inefficient but, in the end, the true eality of dealing with banks and international money markets ruined the viability of Northen Rock. Many building societies that attemptedt to become banks failed because of their shareholder overhead, and some were eventually bought back by such groups as the Nationwide Building Society. The lesson here was that because building societies maintain a constitutional responsibility of serving the interests of their members as opposed to a select group of shareholders, prudent decision-making sustained a high degree of due diligence linked to ethics and the law. This service requires a trade-off between what they pay in interest to savers and that they charge to people wishing to purchase houses.

The problem has been that, in spite of building societies running their affairs in line within a sound constitutional economic principles the drive by banks serving sharholder interests has created, under QE, a massive asset bubble resulting from their direct investment in housing. This has caused a significant rise in house prices and rents. Again it is easy to register the abuse of constitutional economic principles in this business model which operates within the terms of the law. The retort will be, as always, from ministers and bank executives that banks are in business to make money for their shareholders, but then why should such companies expect the constituents to bail them out when their ventures fail? Why is their regulation is so light touch when they have a track record of having generated so much financial chaos.

Banks have generally higher transaction costs because of the fact they are trying to support shareholders whereas building societies can run on transactions and costs structure at least 15%-20% lower than banks. Therefore in the name of efficiency alone banks are less effective in service delivery than building societies and other mutuals.

Interest ratesOne of the more interesting and practical approaches to interest rates has been discussed by the economist Johan Gustaf Knut Wicksell in the form of natural interest rates. These are freely established as a discount on actual returns on investment in order to encourage those wishing to invest to make use of the money and pay the supplier a return. Natural interest rates are not subject to monopoly market intervention by the state which imposes arbitrary rates which distort the free market. We have observed the outcome of this folly in the form of the current basis for monetary policy. For further information on natural interest rates see,

The monetary paradox.

One of the bizarre aspects of monetary policy is the use of interest rates to control "aggregate demand". So centrally imposed interest rates can be raised to discourage investment and consumer credit. Those investing in the currency as interest bearing savings then place money in such accounts resulting in the relative value of the currency rising in the foreign exchange markets. This results in difficulties for exporters and benefits for importers. On balance demand for national goods and services decline although consumers can benefit from declines in the prices of some imports. One of the unexplained claims by monetarists is that raising interest rates therefore reduces inflation while often exacerbating the levels of unemployment that tend to rise. Productivity increases are a way to reduce inflation by creating more for less as has been observed in the information technlogy industries where digital components become increasingly complex and powerful and unit prices fall. However, raising interest rates do act as a diincentive to needed investment. The overall effect of rising interest rates is falling real incomes just as is the effect of unit price rises, or inflation. Therefore by combining high inflation with a solution of high interest rates initially does more damage by reducing real incomes more rapidly. However, under a natural interest rate regime the interest rates remain at a discount on feasible returns to investment resulting in a lowering of the cost of raising productivity to secure subsequent unit price declines and rising real incomes. So the raising of interest rates is an inefficient policy instrument for "controlling" inflation through its impact on aggregate demand.

Starting in 1974, several wars between Israel and other states resulted in the international price of petroleum rising 127% subsequently several other major hikes took place into the early 1980s.

I was in Brazil at the time and by 1975 an attempt to lower inflation by conventional means was blown apart by the fact Brazil, at that time, needed to import most of its petroleum requirements

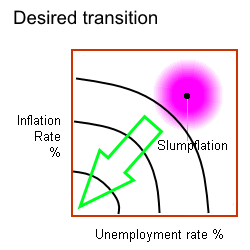

2. The crisis of slumpflation diffused through the world economy combining rising prices with rising unemployment. This inverted the conventional understandings of the relationships between inflation and unemployment which had been established empirically by Phillips, see left, which showed that as unemployment fell towards full employment inflation would increase while moving away from full employmnt and rising unemployment was associated with falling inflation. At that time, around June 1975 I tried to work out how macroeconomic policy should tackle this crisis using the existing policy instrument toolkit. The Keynesian attack on unemployment would be to expand government spending which, if one followed the logic of the Aggregate Demand Model (ADM) would only increase inflation. A Monetarist attack on inflation would have been to raise interest rates to high levels which according to the ADM would radically decrease demand and result in even higher levels of unemployment. So neither of the main convenional schools had answers. This is why I started my work on the Real Incomes Approach while others worked on so-called Supply Side Economics (SSE).

My own work suggested that the main problem was how to maintain real incomes. If one looks at the Phillips curve by moving to low unemployment, real incomes begin to decline because of rising inflation while by moving to high unemployment, real incomes also decline as a result of lack of income due to lack of work. Now looking at the point indicating slumpflation it is self-evident that this location is experiencing an even faster fall in real incomes.

The solution can only be found in a positioning of economic units close to full employment i.e. low unemployment, but by reducing inflation throgh mechanisms that do not resort to Keynesian public debt or monetarist interest rate intervention. In fact it became apparent that the solution should avoid policy decisions based on either the Quantity Theory of Money or the Aggregate Demand Model. However, I was disappointed with the outcome of SSE development which in reality is an ADM-based fiscal policy using marginal tax rates to "encourage" investment. The objective of increasing corporate investment to encourage innovation and reductions in unit costs and therefore prices, was a good one. However, any such policy needs to have policy instruments that maintain traction towards a single well-defined policy objective. For example there was, and continues to be, insufficient attention paid to interest rates which were to remain centrally imposed under SSE. This part of SSE was unstructured and continue to support ADM theory. With a general aim to reduce inflation, ther were no policy instruments to maintain the drive towards increasing productivity beyond some marginal tax breaks

3. Clearly high interest rates would undermine the effectiveness of SSE. This is one reason why, when Reagan attempted to introduce this version of SSE, the government debt imposed by the increased deficit, became the largest in history and public programmes had to be cut back resulting in an overall significant disparity in incomes (see:

Some evidence on the failure of supply side economics ). As a result of the high interest rate policy, many millions lost their homes and family farms and a good deal of policy-related prejudice was imposed on many constituents. In the UK, the high interest rate policy combined with elements of SSE resulted in around 2 million people losing their homes. So the "new" policies that embedded the SSE policy instruments were a real incomes failure for many constituents.

Where we need to go

Where we need to goAn important issue in economics is to separate what happens from some sense of inevitability of events without separating the policy-driven events from those less directly connected. The Philips curve illustrates a curve on the then existing "relationship" between unemployment and inflation. However, this curve is entirely policy-driven and, indeed, illustrates the see-saw nature and instabilities brough about by conventional stop-go policies. The slumflation coordinate is an event triggered by large input price rises resulting from reactions to warfare which led to a significant rise in input costs (petroleum) and the inability of policy to counteract the impacts of this in the short to medium term, in an effective manner. Where conventional policies attempted to do so the rsult was a was significant additional constituent prejudice. In terms of policy which has real incomes as the performance target and indicator there is only one policy direction as shown in the graph on the right. The closer to the origin an economy moves the higher the real income of the population and economic sectors.

This graph in reality is a rough map of the distribution of likelihood of states of enhanced real incomes. In practical terms the extent of real income generation at the macroeconomic level can only be estimated by applying sector demand schedules for local and regional markets according to the specific activities of each economic unit. In the case of global markets, the elasticity of demand for price-setters is well above the market norm so the returns to lower PPR states are enhanced by market penetration, returns to scale, better procurement conditions and the accumulation of tacit knowledge leading to quantifiable increases in performance measured in terms of unit costs of production. The use of the Price Performance Ratio (PPR) as an indicator for companies to adjust their decisions to support the policy objective of sustained or increased real incomes, is described in

PPR-Price Performance Ratio.

Real incomes policy

By establishing real incomes as the policy target, policy instruments need to provide incentives for rational business decision models to ease the improvement in productivity and the distribution of income derived from that productivity to reduce inflation, raise the value of the currency and purchasing power of families and reduce unemployment. However, rather than leave these objectives as lofty vote-generating mantras, businesses need to possess guidelines or rules to help them improve their performance and incomes.

By establishing a market where interest rates are established as a result of free price discovery, savings derived form produtive margins and disposable incomes can operate at the natural interest rate levels helping corporate investment and middle and lower income families acquire needed capital items such as housing.

All economic units are unique so a

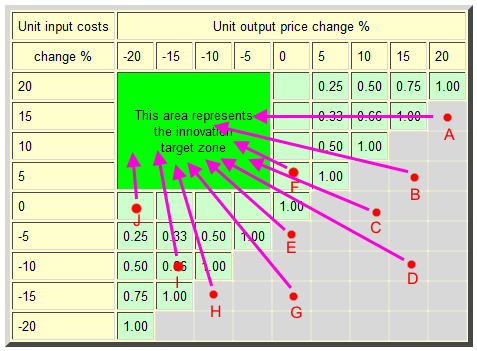

"one-size fits all" approach cannot be contemplated in a serious quest for effective and efficient policy. To understand what companies need to do it is important to understand that the relationship between input costs and output unit prices is able to trace the contribution of the different possible states companies find themselves in to inflation. At the macroeconomic level PPR Maps (see below) provide a strategic oversight of the full array of corporate options and these point clearly to what types of decisions need to be taken to secure a feasible navigation towards the attainment in terms of real income growth. In each circumstance this will depend upon the sector/technologies but they also provide a map of targets for research and development, technology development and the identification of technology transfer requirements. At all times these explicit action requirements and techniques will be improved, in practice, through the refinement of methods applied, that is, the way people apply the technologies relevant to their activities achieved through practice and the further accumulation of tacit knowledge. It is possible by applying well-established performance projection methods, which are fairly accurate, to determine the likely market penetration and cash flows. The PPR maps also provide an indication of the evolutionary transition of where we stand today in relation to the given past and the necessary future states enabling management to more accurately determine optimised timelines for the performance projections.

Price Performance Ratio Maps

Showing where the main growth opportunities lie for corporations

and the time transitions involved

Robin Matthews completed a detailed syudy in the 1960s that showed that in the post-war period the UK economy's high and steady growth could not be explained by Keynesian fiscal policy but the reason, he felt, lay in demand arising out of wartime destruction and an unusually prolonged private sector investment boom. Thus in spite of policy, supply side decision-making was the driver of growth. Around the time of this publication, other more detailed studies, largely on the US economy, established that more than 60% of growth in primary, extractive, industrial, manufacturing and service sectors arises from learning, or supply side phenomena, including technology, learning, technique refinement and innovation. Learning and the accumulation of tacit knowledge are the most important contributors to growth. It is these realities that a real incomes policy makes use of.

Corporate decision analysis and strategiesIt is often stated that policy needs to establish a level playing field. Current policies definitely do not provide this so each economic unit has to dance to the policy tune moulded by a range of centrall imposed disincentives. All economic units, at any point in time, face very different unit costs and feasible unit price circustances according to their sector, size of firm, location and many other factors. A level policy playing field must acknowledge this simple fact and thereby provide a clear pathway for each economic unit to improve performance. Therefore a supply side or real incomes policy needs to accommodate all possible circustances of the economic units. Below is a diagram showing possible locations of different cross-sector economic units within the PPR map. These are tagged as A through J.

The arrows indicate the general direction that corporte decisions should attempt to move the PPR status of a company. The feasible direction will not always be possible because of current technological constraints, but the learning and innovation aspects can contribute significantly to unlocking corporate structures to move in the right direction. The tactics to be deployed often end up as decisions on unit pricing and the projected market penetration resulting from unit price reductions against the incremental costs of implementing actions that enhance productivity. In other words through a tactical application of pricing and incremental costs companies can control their PPR.

Corporate incentive for stabilising or reducing PPRsMost actions taken to improve productivity innvolve a time lapse between the action and securing a "return" on that action and therefore, under the current circustances in the UK, will be associated with various levels of uncertainty and risk assessments. However, the real incomes approach is based on short term compensation for effective pricing by transforming a situation of potential short term losses into short term gains, or a reduced loss, depending upon the tactics applied by the economic unit. Here the real incomes approach through a Price Performance Policy (PPP) is to apply a

Price Performance Levy (PPL). The PPL is not a tax or fiscal instrument, it is a rebate or bonus paid

using corporate funds. In short the PPL is designed to encourage companies to increase their price competitivity by first of all applying a basic Levy to be paid by the company. However, what in fact is paid depends upon the current PPR values. Careful management can reduce the PPL to zero. Therefore unlike taxation the PPL resppnds to the ability of an economic unit to raise productivity and adjust unit prices correspondingly so as to become more competitive. As a result decision-making is constantly concerned with real performance adjustments which create a transarent relationship between physical productivity and the existing input costs and unit price setting of the company.

What has not been covered in this articleThe operation of price performance policy requires a specific data collection infrastructure and I will explain this in a subsequent article; it depend upon state-of-the-art technology. The other point is that I have not explained the options for how performance derived from following the policy incentives can ensure compensatory income for those employed by economic units operating under this regime. This will also be the subject of a subsequent article.

All content on this site is subject to Copyright

All Copyright is held by © Hector Wetherell McNeill (1975-2019) unless otherwise indicated