The vision of early constitutionalists

Although the notion of politics without parties is ridiculed by party stalwarts, our constitutional development shows that amongst the most coherent and transparent constitutional documents were written by those who opposed strongly the whole concept of grouping of politicians into what today we call political parties. Therefore, the notion of politics without parties is not at all alien and it refers to a fundamental component of a more balanced system achieving a broader representation than we have now.

The first major efforts in preparing written constitutional proposals for England were written in the mid-17th Century. An important aspect of these proposals and surrounding considerations was a specific attempt to avoid the formation of political power blocks amongst MPs and within the civil service administration; they sought to avoid the dangers inherent in the formation of political parties. The dangers were seen to be such groupings becoming the foundation of corrupt practice to serve the interests of a factional group and to avoid any such group becoming dominated by financiers or merchants resulting in tendentious legislation favouring the interests of the financiers.

The objectives of the early constitutional documents were to establish a universal suffrage so that the majority could determine the individual members of the representative body or parliament as a true representation of the majority of constituents free from any overbearing influence of powerful factional interests.

It is self-evident that what they sought to prevent, has become current practice in the United Kingdom.

The basic concept

In particular a wonderful concept arose that people should be governed by a Parliament of their popular choice. Such a concept was justified by Colonel Thomas Rainborough, a participant in the Putney Debates organized by the Levellers at the Church of St Mary the Virgin in Putney in the County of Surrey, in October and November 1647. He stated:

“...for really I think that the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live, as the greatest he; and therefore truly, Sir, I think it's clear, that every man that is to live under a government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that government; and I do think that the poorest man in England is not bound in a strict sense to that government that he hath not had a voice to put himself under...” |

This concept, although very advanced for the time, was limited to full male suffrage only.

Almost 360 years ago, the concept of universal suffrage, and other constitutional ideas, were considered by the Levellers to be important in promoting freedom. But many of these were never included in the English Bill of Rights nor in the American constitution, nor were they subsequently taken up and applied in the United Kingdom and nor, it would seem, anywhere else. This resulted in flawed constitutional structures leading to failures to defend individual freedom in an effective manner.

An Agreement of the Free People of England of 1649

John Lilburne, William Walwyn, Thomas Prince and Richard Overton, all of whom were Levellers, had been imprisoned in the Tower of London by Oliver Cromwell. While there, in May of 1649, they penned out a proposal called "

An Agreement of the Free People of England". This document was a proposal for a written constitution for England. 40 years later parts were used in the English Bill of Rights of 1689 and the American Bill of Rights in the American Constitution of March 1789, some 140 years later.

Within the text the authors state that their proposals are not detailed but that redrafting work, aimed at improving (the process of perfection) the content, should be undertaken by faithful representatives of the people.

That we may be free and happy . .

John Lilburne and his colleagues sought to secure fundamental rights for the people of England. In the preamble to their declaration they set out the context of their proposal. They wrote that the nation should be free and happy and that all differences should be reconciled so that all can stand with a clear conscience whilst preventing the prevalence of interests and private advantages. They wrote that actions should not be driven by malice against anyone nor as a result of disagreement over opinions but should be geared towards peace and prosperity for all. They proposed that the free people of England establish a government without arbitrary power and whose action would be bound and limited by law, as would all subordinate authority, with the purpose of removing all grievances.

As one might imagine, such writings, at the time of their release, were considered to be subversive, dangerous and to represent a potential threat to those in power. This was not because what was stated was illogical but rather what was written and stated embarrassed and made uncomfortable those politicians and courtiers who could not countenance government becoming subject to the wishes of the common people. In a sense, these individuals were whistle blowers calling attention and exposing important issues which were never discussed and which remained in force as a result of the subservience of the majority to another group of citizens; a direct measure of the lack of individual freedom. The most significant problem was that moves to increase the freedom of the population through universal suffrage were considered, by those in power, as a threat to their freedoms. The questions of justice and fair treatment of the population was not a consideration of those who considered the existing power hierarchy was something akin to a "natural order". Any attribution of this state as being one of discrimination was countered by the assertion that people needed to remain in their station.

Although at first an admirer of Lilburne, the effective leader of the Levellers, Oliver Cromwell had him thrown into prison on several occasions, indeed, Lilburne spent much of his life in prison. He was, however, never diverted from his mission to fashion innovative ways to chart out courses with the objective of freeing the people of England from what he considered to be forces leading to tyranny. Even today, many of these ideas can be revisited, with advantage, as guides to solutions to contemporary problems.

John Lilburne died at the age of 42 on August 29th 1657, at his home in Eltham, the day he was due back in prison at Dover Castle. He had been visiting his wife Elizabeth and his family; she had just given birth to their tenth child.

It is a comment on the nature of the evolution of our constitution and political environment that there is a statue of Oliver Cromwell near parliament but no statue of John Lilburne.

Some 185 years after Colonel Thomas Rainborough set out what his understanding of representation, limited as it was, it was more a principle, the 1832 Great Reform Act was considered to be the final step in suffrage even by many who were involved in its advocacy. This Act only raised the proportion of voters to around 7% of what would have been considered the voting age population and only included males and property owners.

The role of assetsThe interesting, but seldom emphasized, message in this Act was that only asset holders have the right to influence the outcome of elections to establish representation. Those who had no assets could have no interest or rights in the running of the country. The derived impact of this mentality is that any response by government to the electorate, such as it was, would be related to how policy affected the relationship of voters and their assets. It is clear that in the past, given their general wealth and ability to gain income from share-croppers and other forms of labour, most landowners were voters. Therefore the performance of the economy of land assets, mainly dedicated to agricultural pursuits, were an important determinant of early government policy decisions. Landowners, if they were not MPs themselves, would finance proxies as captive representatives long before political parties arrived on the scene. With the industrial revolution the mass migration of agricultural workers to urban centres in industrial zones led to land consolidation creating larger estates and cheaper food and the establishment of rural-urban logistics networks. Between 1604 and 1914, over 5,200 individual Enclosure Acts were put into place, enclosing 2,800,000 ha or some 28,000 km

2. However, the majority remained in a dependency and lowly status with their income depending on their own toil, no longer working for landlords, but rather, for the owners of industries. Just as landowners considered political representation to be a function of their ownership of land assets so did the growing class of industrialists consider their ownership of industrial capital and cash flow to be the justification for their own political representation.

As can be appreciated the vote is distributed on an individual basis and as a result the means of gaining a more than proportionate influence over power was to collaborate with others of like status and to provide financial support and enticements to the institutional decision makers within government, the principle vehicle being political parties. In this way it was possible for a tiny faction to dominate the political agenda. With time, this process has become easier because increasing numbers of politicians are not land owners or industrial captains but regard being an MP as a job. Since their employment and prospects depend upon their service, first and foremost to the party, they become hapless proxies of those funding parties as benefactors.

Factional mutualityOver time, those in power in any system, come to recognize that although there are rivalries and different interests within their group, they have a mutual interest in remaining in power. Therefore with the development of political parties, ways to avoid upsetting their ability to enjoy the status of remaining in power is to prevent the general population from becoming involved in policy decisions. Therefore, an elaborate system of representation, political parties, procedures and a range of exclusive legal and regulatory acts are made to maintain decision making exclusively in the hands of the "elected representatives" while relegating the constituents to a convenient function of legitimizing the election of representatives while, at the same time, denying constituents any powers of participation in the decisions that affect their lives.

Political party representatives actively promote the notion that it is in the act of voting in elections that the electorate take the most important decisions affecting their lives. However, politicians, in order to safeguard their own interests, status, advancement and income vote in line with party requirements, irrespective of manifesto commitments. The degree to which elected "representatives", who have gained such status by serving party interests, will assiduously represent the interests of their constituents in parliamentary votes in hardly a serious question. Indeed, the state of affairs becomes even more extreme when a party gains a commanding majority in parliament. Their presumption becomes that elections provide parties forming government with the mandate to manage the affairs of the country as if there were on the board of a private corporation. As a result, they feel justified in introducing previosuly unannounced legislation without providing constituents with any opportunity to register their views or to influence this process, even although such decisions will affect their lives.

The conditions giving rise to the need for changeWhen the rotation of power between political parties is associated with relatively stable social and tolerable economic conditions, there is less pressure for change. However, when conditions on the side of economics, for example, sees rising income disparity and specifically a rise in poverty and even pauperism, where increasing numbers of working individuals and families depend increasingly upon contributions from the state to survive, then there will be social agitation justifying a questioning of the competence of the political party system in managing the economy. When the different parties pursue the same economic policies derived from the same flawed economic theory the agitation for change becomes even more urgent.

Today we face such drastic economic circumstances which can be linked to the rise in the adoption of monetarism and advancing financialization in this country during the last 45 years. Covid-19 brought home to most the precarious nature of the economic status of the majority of the wage-earners in this country.

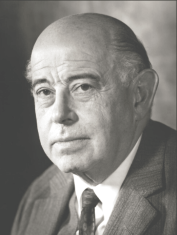

Our political parties have pursued the same flawed macroeconomic policies for over 45 yearsNicholas Kaldor

Nicholas Kaldor Nicholas Kaldor

(1908–1986) |

Nicholas Kaldor was born in Budapest on 12 May 1908. His father was a lawyer and his mother came from wealthy business family. Although his father had wanted him to study law, Kaldor opted for economics. He began his studies at the University of Berlin in 1925 and then after two years moved to the London School of Economics (LSE), from which he graduated in 1930. He remained at the LSE as lecturer until 1947, during which time his colleagues included among others J. R. Hicks and Tibor Scitovski. Responding to an initiative of Gunnar Myrdal, the future Nobel Laureate, Kaldor worked for the United Nations from 1947 to 1949 as the first Director of the Research and Planning Division of the Economic Commission for Europe. He would later hold similar posts in the United Kingdom and other countries. In 1942, Kaldor helped draft the landmark Beveridge Report on Social Insurance, which post-war Labour governments used as the basis of their social policy. Between 1950 and 1955, he was a member of the Royal Commission on the Taxation, Profits and Incomes, and later served as an advisor on economics and taxation to numerous Third World countries, as well as an advisor to central banks and to the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America. Most significant, however, was his role as an adviser to Labour Chancellors from 1964 to 1968 and 1974 to 1976. After completing his two-year mission in Geneva in 1949, Kaldor began to work at Cambridge University and became, as John Maynard Keynes had been, a fellow of King's College, Cambridge. In 1966 he was appointed a professor of economics at Cambridge. His work as a professor continued until 1975, and he held the title of emeritus professor until his death in 1986. Kaldor was the recipient of many honours and various accolades. He was made a peer as Baron Kaldor of Newnham. In his evaluation of Kaldor's work, Professor Luigi L. Pasinetti considered Nicholas Kaldor to be probably one of the most original and most thought-provoking theoretical economists of the 20th century, as well as one of the most radical experts and advisers in the field of taxation policies to several countries.

Ján Iša, "Nicholas Kaldor - One of the first critics of monetarism", BIATEC, Volume XIV, 12/2006 |

|

|

One of the few economists to mount an in depth analysis of monetarism and to conclude the theory was flawed was Nicholas Kaldor who recorded his views in 1970 in an article "

The new monetarism",

published in the Lloyds Bank Review. In it, Kaldor identified two crucial issues: a) the direction of causation between money and output, and b) the ability of

a central bank to control the quantity of money. He reached the conclusion that the monetarists were wrong on both questions.

In our work on the real incomes approach based on microeconomic considerations, that is, seeing the impact of monetarism on the real economy, demonstrates conclusively that the theory is flawed and that Kaldor's analysis is valid. Kaldor came to his conclusions based on a life long experience across a range of fields (see box on right) and his point of view on monetarism should be part of any economist's instruction; of course it is not.

Although the introduction of monetarism as a mainstream macroeconomic paradigm is associated with the government of Margaret Thatcher, under the influence of such advocates as the assertive Milton Friedman, Nicholas Kaldor had withdrawn his advisory support from the previous Labour government in 1976 because of what he considered to be a swing towards the adoption of monetarism under the Chancellorship of Denis Healey in the Wilson government.

Healey had not pursued an industrialization policy along the lines of a logical model set out in Kaldor’s inaugural lecture as professor of economics at Cambridge University in 1966. Kaldor explained in this lecture as well as in several of his research papers that he considered intensification of industrialization vital to the continued growth of the United Kingdom economy. His emphasis was on the UK retaining strong industrial sector because of the logic of technological innovation driving expansion and real growth. He became strongly opposed to the Thatcher government’s monetarist policies, predicting correctly, the destruction of UK industry and manufacturing. Kaldor maintained a focus on the real economy while academia and governments drifted into a range of policies where the real economy, or at least the areas offering most promise for growth, were sidelined by an enthusiastic participation in and promotion of globalization and offshore investment. This, as Kaldor warned, led to a rise in offshore production and rise in unemployment in onshore industrial zones. As a development economist, Kaldor’s constant focus was on the real economy and this fact is reflected in the title of his biography, written by Marjorie Shepherd Turner, as, "Nicholas Kaldor and the Real World".

Like the cynical lack of choice between political parties in the USA, both of which have adopted financialization and a strong emphasis on a destructive monetarism, so Labour and the Conservatives have both adopted monetarism and financialization as the foundation of their macroeconomic policies.

This is why the Blair regime essentially made no difference to the erosion in real incomes of the working class. Then, on winning the 2010 election the Conservative party, rather than opposing Labour government's "temporary" solution of quantitative easing to aid recovery from the 2008 financial crisis, made it a permanent feature to sustain the conditions to pursue austerity, under the guise of paying back debt, while at the same time enriching asset holders who, as a group, tended to be party benefactors.

It is self-evident, that until Labour, or any other political party, opposes the current monetary policies, they will be incapable of offering any genuine alternatives. Therefore the main problem has been that for some 45 years both Labour and the Conservative parties have applied the same monetary policies and as a result they have become indistinguishable on the economic policy front. Both parties and their economic advisers remain committed to monetarism and the aggregate demand model which has resulted in offshore investment, declining onshore investment and falling employment in industrial zones, falling productivity and real wages. The electorate is however, very aware that the asset holding group have benefited for over 40 years from this same economic policy pursued by both parties.

The elephant in the discourseBesides Healey initiating the national swing towards a greater role for monetarisnm in 1975, the 1997 election of Labour saw Gordon Brown, as his first act as Chancellor, proudly making the Bank of England "independent". It is self-evident that he had simply not thought through the dangerous constitutional implications of this decision. His main motivation was more parochial in party political terms. He wanted to avoid the party in government, Labour, being blamed for the impacts of high interest rates such as the disastrous repossessions of houses under the previous Conservative government. This had been caused by the erroneous application of high interest rates to reduce both demand and inflation. This resulted in almost a million individuals losing their homes as a result of the rises in interest rates. Most people thus affected had agreed to mortgage conditions in good faith. However, an inappropriate policy had converted sound affordable mortgages into sub-prime mortgages. This was a factor contributing to the Conservatives losing the 1997 election. But by gaining the ability to deflect any blame to an "independent" Bank of England (BoE), at least the Labour government would be spared the electoral implications of such a problem. However, the constitutional implications of this act were that the Bank of England became less subject to effective oversight by parliament and as a result monetary policy was extinguished as a topic that might be discussed during elections. Since the BoE's brief was to look after monetary affairs, the main constituency of the Bank is made up of banks, insurance companies, hedge funds and other financial intermediaries and as a result the drift in policy was to focus on financial assets values and, indirectly physical asset values, thereby intensifying the concentration of monetarism and financialization in macroeconomic policies including lighter financial regulations. Following the 2008 financial crisis, itself an indication of the failure of financial regulations under the BoE's remit, meant the introduction of quantitative easing, combining close to zero interest rates and rising money volumes based on debt, immediately destroyed the incomes of many relying on fixed income from savings (mainly retired individuals). To understand the mechanisms of these devastating impacts see

"Why monetarism does not work". The impact of quantitative easing provided the evidence to disprove the central tenets of monetarism in the form of the Quantity Theory of Money and the aggregate demand model. However, both the Labour and Conservative parties and their advisers adhered, and continue to adhere, to this theory and the derived policies which, in practice, have been shown to have been a failure in terms of safeguarding the real incomes of wage-earners while enriching those in asset markets.

Shaky evidence in support of QEIn the context of a rising concern with the direction of economic policy and the associated generalized prejudice facing voters and the risk of social agitation arising from the impacts of the intensification of QE in particular, a late but relevant report by the Lords Economic Affairs Committee, entitled, "

Quantitative easing: a dangerous addiction?" raised questions as to the efficacy of QE. This report was late given that QE was introduced as a temporary measure but had been allowed to run for over 12 years with increasing intensity. The "evidence" submitted and recorded in the Committee's evidence sessions did little to hold out any hope that this policy is founded on firm ground. One contributor referred to QE as a policy without a theory and yet others applied a theory, or should I say, "

black box" to predict outcomes, and notably, the BoE's own evaluation department submission admitted that, (paraphrasing)

".... the BoE is still learning about the impacts of QE".

Constituents taking matters into their own hands?In this sort of confusion, it is, therefore, only natural that people who have experienced this economic decadence as a direct result of the combined actions of the two leading political parties in this country, seek ways and means to identify how the country can escape this real incomes trap. Referring back to the lucid and original constitutional declarations of the 17th Century, that warned of the potential negative effects of political parties, it is only natural that serious thought needs to be given to the possibilities of "

politics without parties".

I am editing a section of a book published in 2007 which provides a blueprint of how "

politics without parties" can function. Since the date of publication the High Court separated from the Lords and the country left the EU. Therefore the sections referring to law and the EU are being updated or removed. This will be issued as a pdf document in due course.