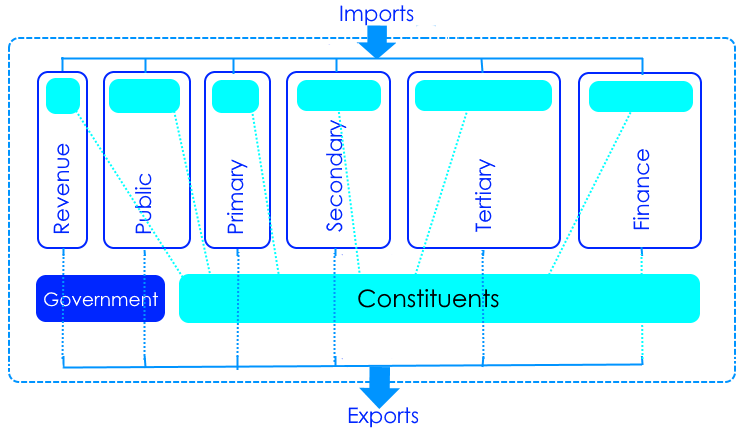

National accounting frameworks are a convenient way of mapping out economic activities into various sectors and then within sectors the flows of goods, services and money between the economic units within each sector and constituents while the constituents are employed either by economic units or provide their services as individuals direct to clients. Sectors are generally divided into the part of the government that receives government receipts in the form of levies and taxes and fines, public services, primary production such as extractive industries, agriculture, fisheries and forestry, secondary production in the form of manufacturing and industry and tertiary service sectors and

finance including financial intermediaries and banks.

finance including financial intermediaries and banks.

At the national level of analysis, given the millions of enterprises and the size of the constituency, national accounts lose a lot of the detail of the actual state of affairs within sectors.

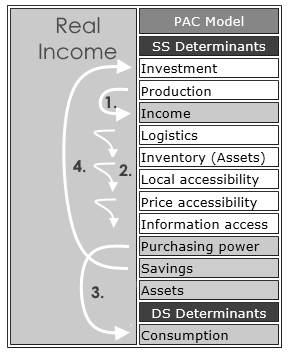

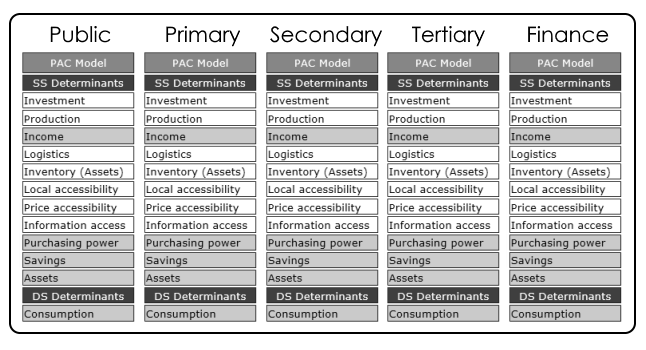

On a sector basis, each sector has a general Production, Accessibility & Consumption (PAC) structure and then each enterprise within a sector, has their own PAC structure. The resulting system is very complex but each cell operates on the basis of a PAC cell.

A single PAC Model is shown on the right.

Accordingly, the general national accounting framework, made up of sectors can be represented as a series of PAC models. An example of this schema is shown below.

Loss of granularity

Loss of granularity

There are two significant limitations on the application of macroeconomic policies based on national accounting frameworks, arising from this complexity, these are that:

- The relevant detail of the cash flows, cash retention and asset holding distribution within and between sectors is an important, but often missing detail

- The missing details are the actual states of affairs of each economic unit and individuals, as the economic constituency

|

This is a natural state of affairs because in the United Kingdom there are around 6 million SMEs in operation where SMEs employ between 0 and 249 people. Companies House reports some 4.5 million incorporated companies. Associated with so many companies distributed through economic sectors and in various positions within supply chains, economic units all face a set of unique and not generalized circumstances with respect to: turnover, size of order books, cash flow status, profitability, competence of owners, managers and work forces, levels of organization, technologies deployed, techniques used, general performance when compared with state-of-the-art best practice, quality of output, unit costs, price competitivity, market segments served, information management and many other bases for assessment.

Free markets and the freedom to pursue objectivesFrom an economic standpoint the term freedom when applied to markets refers to the relative levels of impediments to economic units pursuing their objectives. In a constitutional or legal sense the only impediment is normally that economic units can pursue their objectives as long as they do not impose constraints on other economic units to pursue their objectives even when in the same sector and providing similar goods and services. Free markets are "made" by the transactional nature of buyers evaluating the comparative quality of goods and services from the standpoint of accessibility criteria:

- reliable information on products and services

- affordable unit prices

- physical deliverability

- access to post-sales support

Companies and individuals supplying goods and services, according to their operational states, satisfy consumption needs to varying degrees to the extent that they meet the criteria of quality and accessibility. The degree to which quality and accessibility criteria are met depends upon the freedom of the economic units and individuals supplying products and services to follow development pathways according to their specific conditions and capabilities without being impeded by other producers or by economic policy constraints.

Why conventional aggregate demand management is inappropriateBased on "average conditions" within a sector it is self-evident that most will not be of average status. All companies, and consumers can benefit from all making progress in terms of productivity and efficiency, but in order to achieve this, policies need to responsive to the fact that all companies start out, at any point in time, from very different conditions.

Explicit & tacit knowledge

Tacit knowledge can only be acquired as a result of direct exposure to some process where the ability to master it depends upon practice and repetitive application. Explicit knowledge is that which is more easily transferred from one individual to another in the form of symbols, figures, the spoken word and human communication media. More information can be obtained on role of tacit and explicit knowledge in the economy in, "Tacit & explicit knowledge" |

|

|

Solow

3 and Arrow

4 provided a considerable amount of evidence to demonstrate that some 80% of economic growth is the result of learning leading to changes in technology and techniques used and such beneficial change, arising from innovation, is the facilitated and motivated by the accumulation of information from experience and the accumulation and application of tacit and explicit knowledge (see box on right). As can be appreciated, the way in which each company or individual gains and applies this knowledge involves various time lines affected by the circumstances of each one. It is self-evident that policies need to be geared to shaping the economic environment for companies and individuals so as to facilitate the removal of all impediments to their progress.

Unfortunately, Keynesianism, monetarism and supply side economics (KMS policies), and it would seem, modern monetary theory, are all top down centralized and market intervention policies. Because their adjustment of economic conditions is achieved through significant interventions to influence aggregate money volumes and interest rates results in such policies imposing impediments on some while affecting other less. The invariable outcome of KMS policies is to create winners, losers and those who remain in a neutral policy-impact state. Such outcomes have not only affected the economic constituencies but also the social constituency.

National growth is the aggregate result of enterprise-specific decisions

The particular investment opportunities open to different companies in different sectors provide a very wide range of potential payback in terms of return on investment ranging from very long term and low returns to some over shorter terms and higher returns. This reality is disturbed by the raising of base rates resulting in high commercial interest rates to levels that curtail any opportunity for some companies to invest to improve productivity. In such cases the use of savings can represent a rational option. However, at the other end of the macroeconomic stimulus options as a combination of low interest rates with higher lending, but not always low enough commercial interest rates in a depressed market. The depression is the result of diversion of money into assets and this curtails investment in higher productivity options. Since inflation is not caused by money volumes, the use of centralized interest rate setting, and "money volumes" to control inflation, are arbitrary and disruptive to the requirement of a steady trend in investment for productivity. At either end of the policy swing aggregate demand policies impose conditions that are inimical to creation and innovation, the foundations of real economic growth.

KMS policies, therefore, do not support free markets and because the policy itself impedes the freedom of many companies to achieve their objectives as a result of arbitrary market interventions.

Nominal and real growthKMS policies see economic growth as the equivalent to the rise in value of "demand" and the resulting turnover of the economy. In a world of rising populations and limited natural resources the more significant target is real economic growth. This is measured as a direct result of productivity and not, initially, in currency terms. Through adequate changes in the way production and services are generated and delivered is it possible to reduce resource inputs and waste and to produce more for less as a result. If the balance between input resources and their total costs end up with lower unit costs, companies have the option to gain more market share by reducing their unit prices.

Innovation promoting real economic growth

In 1965, Gordon Moore of Fairchild Semi-conductors published an important paper “Cramming more components onto integrated circuits” 2, concerning the trends in the feasible number of transistors that could be placed into an integrated circuit. The significance of this technological fact can now be seen in the transition towards smaller device logic requiring less energy and physical resources to build them. Already the costs of production, once over the R&D recovery periods is and will continue to result in lower output prices not only on a profitable basis but resulting in a significant rise in the purchasing power of disposable incomes assigned to this type of product. The result is a rise in the real incomes of companies and consumers. It is self-evident that this ability to set prices in this way has no relationship to aggregate demand as described by those who base policies on the Aggregate Demand Model. The reality is that those companies who are able to reduce their price performance ratios (PPRs) will be the companies who excel. Other sectors, deploying other technologies have different rates of feasible gains in productivity, this is natural. But in all cases, incentives to help companies moderate PPRs helps maintain the focus of management of productivity and market penetration.

Source: McNeill, H. W., " What causes inflation", Charter House Essays in Political Economy, HPC, December, 1981, ISBN: 978-0-907833-14-7. 2 Moore, G. E, “ Cramming more components onto integrated circuits”, Electronics, Volume 38, Number 8, April 19, 1965.

|

|

|

As a result their nominal revenue will increase as a result of the benefit consumers have gained in terms of being able to purchase more output with the same nominal disposable income. In real income terms both the company and their customers have gained a rise in their real income and the replication of this process across the economy results in a growth in real income at a higher rate than any growth in "money volume".

The fiscal paradoxWhere governments raise loans to pay for aspects of investment in public services or infrastructure the common justification is that this will be recouped as a result of the economy growing. The desire on the part of governments or treasuries is that by building up money volumes the GNP will rise to result in higher tax returns. An underlying justification, arising from Keynes original intent is to raise employment (reduce unemployment). In both cases, the only basis to make such changes sustainable is on the basis of a self-supporting growth based on real growth through rises in productivity of physical production and service activities. The most obvious example of this process has been the significant technology driven increases in productivity in the information technology and telecommunications industries manufacturing and services sectors (see box on the right). This has been associated with pricing decisions that have followed a downward trend which has resulted in people's real incomes or purchasing power, for such devices, increasing. So supply side management and decisions making have been the main driver of consumption and the funds used in that consumption have come from the production, or, supply side.

The monetary paradoxOn the side of monetarism, it is evident that the model used to justify decisions on monetary policy, the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM), had no coherence or capabilities to predict outcomes because key determinants of outcomes were missing from the formula. (see

"A Real Theory of Money"). While the economies have struggled under medium to high interest regimes for many years

Boxed-in

The lack of attention to productivity can be seen in the preoccupation of policy makers with government revenue-seeking status or "fiscal neutrality". This translates into regarding government and the rest of the economy as fixed sized boxes or accounts. Government revenue drains money away from the economy box and pours money back in via public services. The draining of funds from the economy box often has a "demand management" role to reduce purchasing power and disposable incomes when the government erroneously imagines that inflation is related to money volumes.

There is very seldom enough emphasis given to incentives to raise productivity in the economy and convert this to real incomes through price moderation. This could translate into lower taxation requirements to secure the same level of public services activities by requiring reduced nominal sums of money to provide the same levels of public service.

The so-called Laffer curve is often used to justify movements in the levels of taxation linked to maximizing government revenue. Without adding the productivity determinant to the activities of government and to the economy, none of this provides adequate guidance on which policy targets and instruments are the best to secure real economic growth.

This boxed in static accountancy, national accounts approach, is an inadequate basis for decision analysis on macroecomomic policy questions. It limits the potential for real growth because it ignores the immense heterogeneity in conditions facing economic units. Each economic unit needs to be able to operate unhindered by one-size-fits-all "policies"; there is a need for policies that enable companies and individuals to have the freedom to apply adaptive intelligence according to their needs. |

|

|

hampering investment to promote productivity the failure of the QTM became apparent in its complete failure to predict what would happen under quantitative easing (QE). This was predictable in any case as a result of the Japanese experience in previous years. However, government insisted this was the solution to recovering from the last financial crisis caused by excessive debt and sale of banks purchasing and holding worthless securities in the form of derivatives. QE did not solve this problem because much of the low interest funds was channeled into assets. The Real Theory of Money (RTM) which has replaced the QTM demonstrates how assets undermine real incomes and depress the economy.

The productivity, innovation and policy challengeNot all economic activities deploy technologies that have the same potential as information and communications technologies (ICT) to raise their productivity, but all sectors can improve their productivity by various means. One of the most remarkable facts is that if the range of practice in each sector is examined there are normally only a small proportion of economic units that are deploying state-of-the-art technologies and best practice relevant to their particular product or service output. Their productivity levels are in some cases more than two or three times higher that other units in the same sector. On average it is estimated that in most sectors best feasible practice is at least twice the level of productivity attained by average practice. Therefore without any advances in technologies, which will of course continue, it is sufficient to promote the take up of existing state-of-the-art technologies and techniques to revolutionize economic productivity. This creates a need for more effective diffusion of information concerning and access to these technologies. The fact that state-of-the-art technologies have well-established track records reduces, to a considerable extent, lack of transparency and precision of calculations used to assess the feasibility of adopting such systems through investment.

The required policy challenge is for policy targets to move from "demand management" to the more practical objective of stimulating adoption of state-of-the-art technologies. This is an important foundation of promoting "real incomes" growth by abandoning the current fixation with "money volumes" or debt. The application of a command and control interest rate policy based on the "average" undermines the objective because any selected interest rate will be arbitrary for most economic units and therefore prejudicial to the development of productivity. Policies need to encourage, across the board, an environment that places no impediments on companies, at any level of practice and know how, and who wish to improve their productivity, to be able to do so. This also means, governments should not attempt to pick "winners" but should permit all companies and individuals with a opportunity to develop into productive and sustainable operations.

In this way it is feasible to escape from the money volume demand management paradigm that destabilizes the lives of many economic constituents by running the economy as if it were a national account that is run on the basis of balancing money flows between fixed sized boxes where the purchasing power of the money stagnates because of the lack of productivity (see box on left).

1 Hector McNeill is the Director of SEEL-Systems Engineering Economics Lab.

2 Moore, G. E, “

Cramming more components onto integrated circuits”, Electronics, Volume 38, Number 8, April 19, 1965.

3 Solow, R. M., “

A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth”, pp. 65-94, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 70, No. 1. Feb., 1956

4 Arrow, K. R., "

The Economic Implications of Learning by Doing", pp. 155-173, The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 29, No. 3. June, 1962

All content on this site is subject to Copyright

All copyright is held by © Hector Wetherell McNeill (1975-2020) unless otherwise indicated