The Quest for GrowthThroughout the world the recent financial crisis has resulted in economists and policy-makers pondering over how to improve the productivity of their economies so as to "grow" out of recession, debt or under-development. The quest for growth is universal and applies to all economies.

Whether one is concerned with the stimulation of exports or a national economic growth, key elements include:

- higher productivity

- sound pricing policies

- a stable currency

|

These elements together can directly determine the purchasing power of incomes within the national market and the relative attractiveness of nationally produced goods and services in export markets. The relative value of the currency, expressed as an exchange rate, is a determinant factor of unit prices in export markets.

Conventional growth policies

The operation of most conventional macroeconomic growth policies is based on the stimulation of so-called aggregate demand and the response by economic units based upon decisions driven by the profit motive. The stimulation of demand is accomplished by monetary policy using interest rate-setting and money volume, fiscal policies based upon government revenue seeking and expenditure as well as the variant involving government debt associated with Keynesianism.

The outcomes of these policies tend to be a growth in nominal output but a failure to have any enduring effect on productivity with unit prices for export failing to generate the hoped-for growth in exports. I should add that the recent policies of quantitative easing with centrally-imposed low interest rates has not improved the situation but this has diverted funds from the all-important investment in higher productivity technologies and redirected funds into assets, draining the real economy of its guarantee of future operations. The result has been that for the last 70 years the balance of payments of the United Kingdom economy has steadily declined reaching its worst situation recently (1st Quarter 2015). Whereas monetary policy has been supporting a hidden currency war, we can see that after 70 years there has never been a sustainable gain in exports from the UK arising from the constant and disastrous devaluation of the pound.

Supply side economics surfaced in the wake of the petroleum crisis of the 1970s as an approach to handling slumpflation and as an alternative macroeconomic policy. This proposed lower marginal rates of taxation to stimulate investment and the production of lower-priced goods and services. When applied in practice, during the Reagan administration in the USA, it resulted in some real growth and a fall in inflation, more related to high interest rates. This policy also generated one of the largest Federal deficits in US history impacting government services as well as generating significant disparities in the growth of incomes of high earners and low income groups.(see

"Some evidence on the failure of supply side economics")

In summary, because the economic and social constituencies have such different requirements and objectives, the monopoly centralized market interventions by the state in interest rate setting, money volumes, taxation levels and expenditure as well as debt could never accommodate the range of requirements within the economic and social constituencies. This has led to suboptimal growth. The typical outcome was the generation of winners, losers and those unaffected by policy. There are many additional explanations for these outcomes but the most obvious cause is to be found in the profit paradox which results in a significant misallocation of resources in most economies leading to inefficiencies and slower than potential growth.

Two major areas of operation of conventional economic policies containing the main flaws in economic logicUnder the weight of conventional policies suboptimal growth arises from distortions in resources allocation arising from:

- The creation of the profit paradox by fiscal policy

- Monetary policy and real currency value

The creation of the profit paradox by fiscal policy

Business management practice operates under business rules that demand compliance with government revenue seeking activities through tax payments within legally based regulatory frameworks for accounting and audit. Profit, within this framework is:

- the target for corporate taxation

- the measure of corporate success

- dependent upon containment of human resources costs

Fiscal policy has imposed lower levels of productivity in the UK

The central focus on profits creates conflicting allocative constraints which result in mutually contradictory management adjustments which need to contend with the minimization of taxation obligations by minimizing profits, the achievement of adequate returns for shareholders through the maximization of profits and the containment of wage rates and movements to safeguard profits.

This creates a situation where it is logically and mathematically impossible for managers to optimize resource allocation to maximize benefits in line with the specific conditions and objectives of each firm. After all, constraints such as tax and interest rates are set arbitrarily by government aligning with the needs and conditions of all but a few companies This is one of the reasons why advanced state-of-the-art-technologies, which can generate significant rises in productivity, are not fully deployed, leading to the existing operational productivity frontiers being well below the potential.

Besides constraining business ability to achieve higher productivity the allocative constraints create a strong motivation for a proactive substitution of labour, an active constraint on wage increases of employees and a growing incentive for corporate tax avoidance and evasion, already estimated to involve significant financial resources.

As a result the long term trend, for some time now, has been for real wages to decline and for profits to rise as a percentage of national income. The outcome has been an evolving cost of living crisis that affects an increasing percentage of the social constituency, now eroding the status of middle income families. Fiscal policy, because of the profit paradox, cannot sustain a positive systems consistency.

Under these pressures the meaning and role of profits has become perilously ill-defined and abused culminating in repeated disastrous business, macroeconomic policy and financial intermediation failures in so-called free markets within which economic activities continue to be driven by the "profit motive". We have come full circle only to re-enter an age where the role of profits has become so perverted as to take on the role that provided Karl Marx (1818–1883) with the opportunity to refer to profits as "excess production" robbed from the workers.

Joseph Schumpeter's perspective on profits An article by Peter Drucker

2 on the Forbes site entitled,

"Schumpeter & Keynes" compares the approaches to economics adopted by Joseph Schumpeter

3 and John Maynard Keynes.

In one section Drucker describes Schumpeter's view on the role of profits as the foundation or guarantee of future activities and employment. The significance of this view arises from the fact that Schumpeter's role for profits, bears little relationship to their currently perceived role but, in my view, it presents a key to straight thinking; an imperative. By limiting the role of profits to that identified by Schumpeter it is possible to alter the accountancy norms so as to terminate the contention between business success and wages as well as to ensure government revenue rises to realistic levels. This can best be achieved through a real incomes approach policy such as Price Performance Policy, described at the end of this article.

Monetary policy and real currency value

Besides fiscal policy as a problem area in macroeconomic management, monetary policy is the other main constraint on a more efficient economy. Monetary policy operates on the basis of imposed alterations in money issuance (volume) and interest rates. The main operational factor impacting microeconomic decisions is the interest rate which is set arbitrarily by the Central Bank (Bank of England). The work "arbitrarily" is used with qualification in the sense that it is not possible to establish a single interest rate that responds to the requirements of each economic unit or social constituent. As a result, even with banks introducing weightings on interest rates related to their assessment of risks associated with loans, the interest rate regime is not optimized to the needs of individual enterprises.

OperationsCounter-inflation policyRaised interest rates are applied to reduce "aggregate demand" so as to "squeeze" inflation out of the economy. The impact is not only a raising of the costs of consumer credit but also the raising the costs of investment based on loans. Depending upon consumer disposable incomes and the potential returns to investment in economic units there will be a significant differentiation in the impacts of interest rate rises. The impact of higher rates will impact consumers and economic units in a differentiated way so the policy cannot secure a positive systems consistency; interest rate-setting discriminates against specific sets of consumers and economic units, by default.

In terms of reducing the aggregate demand then the component made up of consumer expenditure provides a demonstration that a raised interest rate policy impacts aggregate demand by reducing it.

The issue isn't inflation it is real incomesThe fundamental impact of inflation is a fall in real incomes and therefore any corrective policy should be providing incentives for operational changes at the microeconomic level that secure real incomes or raise them. The factors that secure real incomes are:

- Nominal income

- Productivity

- Pricing policy

Note that these factors are what determine the "strength of the economy" by establishing the purchasing power of the currency as a result of rising accessibility and consumption of goods and services produced at steady or falling unit prices. The ability to operate competitive pricing policies depends upon rational investment in technology and human resources. The error made in the aggregate demand model (theory), as well as in monetary policy, is the failure to acknowledge that inflation arises solely as the result of the operational transactions carried out by each economic unit in the economy. Specifically, inflation is created by the ratios of increase in unit output prices to the increases in unit input costs. Therefore policy should be focused on the facilitation of management decisions in bringing about appropriate unit price responses at the level of the firm. Policy should not be focused on arbitrary interest rate-setting.

Although high interest rates have the desired impact on consumer "demand" they actually frustrate the ability of companies to respond through investments to raise productivity; higher interest rates raise the cost of investment. In this context higher interest rates produce an input inflationary pressure on companies and constrain the development of more productive operations. This state of affairs reduces the ability of business to respond optimally so as to manage their productivity and pricing issues. Companies attempting to become more competitive under such circumstances face significant challenges.

Currency value and exchange ratesThe setting of interest rates has an impact on the movement of capital, and especially foreign capital, in and out of the pound sterling. So higher interest rates attract investment in interest-bearing accounts both by individuals and corporations. The associated impact of this dynamics is that the exchange rate tends to follow interest rates. This creates difficulties for exporters under policy-imposed conditions of a raised cost of investment finance.

Counter-deflation policyMonetarists have created a taboo in relation to deflation, that is, falling unit output prices of goods and services. First of all, an effective counter-inflation policy, will after some time, in a very inefficient way, encourage a fall in inflation or a state of deflation, that is, a continual fall in unit output prices. Within the real economy falling prices encourage competition and rationally focused investment in technology and human resources so as to create the means whereby accessible prices can be secured at a profit. But here we run into the problem with "profit" set out above in the context of the profit paradox.

Deflation benefits the real economy and threatens the asset economyThe operation of monetary policy has differential impacts on the social and non-financial economic constituencies but tends to constantly benefit those dealing with financial assets in general and in particular the banks who are used to support monetary policy operations. The "fear" of deflation is one more related to the value of assets. As raised interest rates begin to impact consumer demand and inflation rates decline there comes a threshold at which rather than observing declining rates of unit price increase we see falling unit prices or deflation. In association with declining interest rates the interest received on bank held savings declines impacting those on fixed incomes and financial institutions such as pension funds. In an attempt to sustain the income originally based on interest rates, financial portfolios diversify by taking positions in commodities, real estate, stocks and shares and an ever-increasing range of derivatives. One of the associated manipulations related to the profit paradox is that corporations begin to purchase their own shares in an attempt to increase their value as an asset.

Whereas the real economy becomes very competitive in initial deflation phases the financial dealings in the asset economy initiate an inflationary process in assets (bubbles) and in particular commodities including agricultural produce, food, energy and minerals.

The impact of monetary policy is to create arbitrary difficulties for the real economy at all levels of inflation.

"2% inflation" is not price stabilityOver the last 70 years the Bank of England, like other central banks, in an attempt to steer away from deflation, has set the inflation target of policy to around 2%. The justification is couched in terms of gaining price stability so as to provide business predictability. However this 2% target is not price stability and represents a devaluation of the pound sterling of over 18% each decade. As a result the purchasing power of the pound sterling is today worth less than 2% of its value in 1945. With such a significant fall in the value of the pound, one would expect to see the UK as a major export economy. However, current account trade deficits have increased for a very long time and by 2015 the UK recorded the highest current account trade deficit. The policy has been a resounding failure and this is a direct result of interest rates being set arbitrarily by monetary policy. The asset economy has benefited while the real economy has been unable to secure a growth in productivity sufficient to make more British products and services competitive enough. This is a direct result of an inability to sustain appropriate investment in technology and human resources.

Market generated interest ratesInterest rates need to be established as market prices for funds which vary according to the quality of each proposed financial transaction under consideration varying from a house mortgage to corporate capital investment. In the case of corporate capital investment the nature of the activity, state of the art technological capabilities, existing human resource capabilities and the configuration of an investment can provide a rational assessment of potential return and therefore a range of interest rates that are appropriate for each company depending upon assessment of risk associated with a loan. As a result interest rates need to reflect the supply or rather the drawing up of investment projects by businesses or loan requirements by consumers.

What is required?The fundamental requirement is that the macroeconomic components of fiscal policy and monetary policy be restructured so that policy can be more directly responsive to corporate needs. Policy needs to provide incentives for more efficient resources allocation on the part of companies according to their specific conditions, objectives and access to resources. Policies need to permit managers to adapt policy indicators to values that reflect what is feasible and beneficial to each economic unit. This transition requires:

- the elimination of the profit paradox

- a reconsideration of the relevance of tax considerations to corporate resources allocation decisions

- a modification in monetary policy so that it responds fully to the needs of the real economy

Eliminating the profit paradox

Eliminating any confusion as to what profits are for, boils down to identifying the basic processes that can:

- secure an income for the founders of economic units, their shareholders and employees

- generate resources for investment in better designs of products, services and processes

- generate resources to serve current operations

Box 1

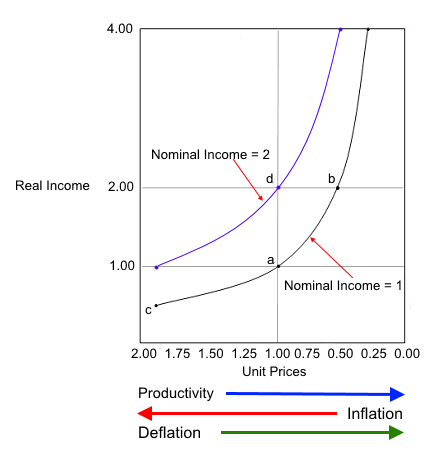

Nominal Incomes, Inflation, Deflation, Productivity, Unit Prices & Real Incomes

The measurement of real incomes is more precisely determined with respect to the circumstances of any particular individual.

Thus one can measure real income in terms of individual nominal income (iNI) and the prices paid by that individual as individual average unit prices (iAUNP) as a basis to provide an individual real income level (iRI).

Thus iRI = iNI/iAUNP ........... (1)

Where

iRi is an individual's real income;

iNi is an individual's nominal income (disposable)

and iAUINP is the average unit prices paid by that individual.

If the iNI is fixed in the short term at say 1.00 (see graph above) and one takes a starting position where the average unit nominal price is 1.00 then the instantaneous real income associated with these two variables is also 1.00. See point a in the graph.

Inflation

If individual average unit nominal prices rise, in the short term, real incomes fall. For example, a doubling of the individual average unit nominal prices ends up with the individual real income level falling to 0.5 as shown by point c in the graph.

Deflation

A halving of unit average nominal prices to 0.5 increases the individual real income level to 2, as depicted by point b in the graph. That is, real income is doubled.

Growth in nominal incomes & real incomes

Rising nominal incomes do not necessarily result in higher real incomes. Thus the real income effect of unit prices shows that the real income of someone with a nominal income of 1.00 but paying an average price of 0.5 is the same as someone with a nominal income of 2.00 but who is paying an average price of 1.00 - compare points b and d.

Inflation & deflation

Inflation is a state of affairs where unit prices are rising so that at any nominal income level, purchasing power and real incomes decline (see above). Deflation is a state of affairs where unit prices are falling so that at any nominal income level, purchasing power and real incomes rise (see above).

Productivity & unit prices

The ability to achieve sustained rises in real incomes depends upon an ability to sustain a growth in nominal incomes associated with falling unit prices or upon falling unit prices alone. Therefore rather than rely upon the aggregate demand model (ADM) and monopolistic interventions such as interest-rate setting or taxation and government expenditure, the Real Incomes Approach places more emphasis on productivity as the means to reduce unit output prices and to control inflation so as to increase growth based on rises in purchasing power and real incomes.

Note that the item iRI can be equated to the quantity of goods, services and money purchased by an individual i.e. iQgsm, thus:

iQgsm ~ iRI = iNI/iAUNP .................. (2)

Thus real income appears is equivalent to the purchasing power of income expressed as the quantities of desired goods, services and money which can be purchased for a given nominal income.

Source: Working notes on Real Income, SEEL-Systems Engineering Economics Lab (1983-2015).

|

|

|

Real incomes The failures of fiscal policy and monetarism can be unified in the failure to protect real incomes of individual constituents, employees and shareholders in an optimized fashion. More fundamentally these policies impose unacceptable constraints on the management of economic units prejudicing the attainment of higher levels of performance because of the profit paradox. The emphasis within the fiscal framework, therefore, needs to be more on the benefits accruing to people associated with economic activities as incomes and not profits per say. Within the monetary framework, more emphasis needs to be placed on sustaining the value of the currency or purchasing power. The standard approach of defending "price stability" by tolerating 2% inflation has been demonstrated to be ineffective from the standpoint of guaranteeing growth. Monetary policy needs to change to be the guardian of real incomes by safeguarding the value of the currency.

Fiscal policy needs to be substituted by mechanisms that increases the ability of the social constituency to pay tax based upon their contributions to an increased performance of economic units and general economic activities in the creation of real incomes, that is, transactions in a currency that maintains a more stable purchasing power.

The current monetary and fiscal arrangements need to be replaced by a common course of action that secures and helps raise real incomes.

The Real Incomes Approach

Theory The Real Incomes Approach to economics is a general theory of the economy that enables the formulation of policy options that concentrate on a new microeconomic paradigm that support business rules that improve the likelihood of the achievement of better resource allocative efficiency. The new business rules are coherent with the macroeconomic objective of enhancing real incomes so as to achieve a positive systemic consistency. This is in marked contrast to conventional monetary and fiscal policies. Although the Real Incomes Approach is a general model of the economy it in fact operates as a growth model because it stimulates and provides a positive incentive for increases in productivity and a rational distribution of real incomes.

The cause of variations in currency valuesThe Real Incomes Approach is based on the PACM-Production, Accessibility, Consumption Model (see:

The PAC Model of the economy) and not on the so-called ADM-Aggregate Demand Model. The ADM model sees the stimulation or reduction in aggregate demand as the central operation of macroeconomic policy and the value of the currency becomes the consequence of outcomes beyond the control of the economic constituency. The Real Incomes Approach relates the value of the currency directly to economic productivity. Thus inflation or deflation are strictly a supply side phenomenon and not normally directly related to market demand or supply market conditions. In this context conventional policies to control inflation are all external to the specific concerns of each company and are broadcast top-down. However, the actual cause of inflation or deflation is the rate at which firms pass on variations in their input costs as unit output prices. Such activities cannot be impacted in a beneficial and predictive sense through centralized policies. Depending upon the productivity of operations, feasible unit output prices and the purchasing power of the currency (the value of the currency) will vary.

Necessary changes in accountancy details

The necessary transition to solve the profit paradox within the fiscal framework involves the some simple transformations in accountancy norms and regulation details. The objective is to facilitate resources allocation so as to achieve the highest feasible return to operations supported by investment in technology and human resources. This is achieved by eliminating conflicting allocation objectives as well as to assess the relevance of tax considerations at the stage at which decisions are being made on resources allocation and the drawing up of accounts. The corporate taxation and accountancy framework is so divisive that significant efficiencies can be realized by eliminating corporate taxation from the decision analysis model. This is not to say government revenue raising is not an essential requirement in a modern economy but corporation tax is a very inefficient and disruptive way to raise government revenue. By eliminating corporate tax considerations we are left with six basic categories of quantifiable accounting aggregates:

- Corporate revenue from sales

- Income of individuals associated with the company

- Current operational costs

As mentioned, the profit category can be redefined as investments in technology and people (in the Schumpeterian sense). So the accounting categories can be expanded to seven:

- Corporate revenue from sales

- Income of individuals associated with the company

- Current operational costs

- Cash

- Assets

- Investment in technology

- Investment in human resources

Creative transformationMargins in excess of distributed real incomes and operational costs represent funds that can be invested in innovation or expanded operations, saved or used to purchase assets. Sustainability depends to a large extent on the degree to which investment is geared towards a creative transformation that improves efficiency and productivity through investment in technology and human resources so as to maintain a sustained income and employment.

Increasing the focus of monetary policy on the needs of the real economyThe fact that higher interest rates constrain consumer demand but introduce an inflationary pressure on input costs (finance), export activities are constrained because of a raised exchange rate associated with the demand for the currency associated with foreign investments in bank interest-bearing products or savings accounts. This constrains investment in higher productivity activities. On the other hand the deficits in productivity investment are manifested in the fact that exports do not improve with reductions in interest rates or lower exchange rates because of inadequate productivity. During such phases low interest funds tend to be used for investment in low risk physical assets as opposed to interest-bearing products.

Monetary policy, as currently practiced, does not relate currency value to productivity; currency value is related to base line interest rates set by the Bank of England. However, in order to raise and sustain real incomes, policy needs to create a mechanism whereby managers can invest in productivity in a way that provides predictability in the value of the currency as reflected in purchasing power or real incomes. This requires the application of a paradigm that provides a transparent relationship between productivity and price movements (inflation, stability or deflation). This means that in practical terms policy needs to encourage a proactive effort on the part of companies to reflect productivity in terms of unit output prices and product and service quality. Thus the focus becomes the productive transformation within each company and the relationships between unit input costs and unit output prices.

From prescription to relevanceIt is not possible for any government to prescribe centrally imposed values to conventional policy instruments in a way that permits adaptation to the specific conditions of the economic constituents.

The PPR equations

Inflation

Under inflationary conditions the degree and direction in which a company influences price inflation is determined by the Price Performance Ratio (PPR) (see ). This is the ratio of the percentage increase in unit output prices to the percentage increase in total unit input values over a given period of time:

PPR = (100(dPo)/Po)/(100(dPi)/Pi)

PPR = (dPo .Pi)/(dPi.Po) ..... (1)

where:

dPo is the increase in unit output prices during the period and Po is the unit output price at the beginning of the period; and dPi is the increase in total input values per unit during the period and Pi is the unit input value at the beginning of the period.

Deflation

Thus under deflationary conditions the degree and direction in which a company influences prices can be measured as the ratio of the percentage fall in unit input costs to the percentage fall in unit output prices over a given period of time. Note that this is the inverse of the equation 1 above and it is therefore of the following form:

PPR = (100(dPi)/Pi)/(100(dPo)/Po)

PPR = (dPi .Po)/(dPo.Pi) ..... (2)

where:

dPo is the decrease in unit output prices during the period and Po is the unit output price at the beginning of the period; and dPi is the decrease in total input values per unit during the period and Pi is the unit input value at the beginning of the period.

|

|

|

The excessive control over centralized policy instruments defaults to a state of affairs where, in reality, the economy is not being managed effectively. The Real Incomes Approach, in relating productivity to price performance avoids the mistake of prescription by providing incentives to encourage the economy and all economic units making up the economy to "move in the right direction". The right direction in this context is for resource allocation to be designed to maximize the real incomes of all associated with companies as a result of quantitative improvements in performance. The policy cannot prescribe what productivity levels should be but it can make the improvement in productivity in any specific circumstance a priority for all economic units by ensuring appropriate decisions are compensated. In this context appropriate decisions change operations to enable companies to contain price rises to the extent of freezing them and even reversing them so as to secure a rise in the value of the currency and a rise in real incomes in general. This can be achieved by making use of the specific price performance of companies to provide guidance on pathways to higher productivity.

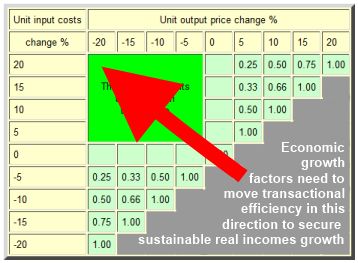

Price performance and the Price Performance Ratio (PPR)

Price performance, the relationship between changes in input costs and the response in terms of output prices helps identify how a company manages product and service value for money. Does a company absorb input inflation or does it pass this on to customers? Depending on how a company manages pricing can influence the contribution of that company to the status of the currency in terms of value by its impact on purchasing power or the real incomes of customers. Relative prices also determine the range of options customers have in satisfying needs within the constraints of their real disposable incomes. Indeed, in contrast to the aggregate demand model which sees "demand" as the determinant of inflation or deflation, here the exclusive source of inflation is the pricing moves by companies. Price performance is the dynamic process of the relationship between variations in unit input costs and unit output prices. A useful measure of the contribution of a company to the value of the currency is the Price Performance Ratio (PPR) see the box on the right). PPRs are the ratio of variations in unit output prices to variations to unit input costs so under inflationary conditions a low PPR (less than one <1.00) signifies that a company absorbs inflation and a higher PPR operation (more than one >1.00) increases inflation.

It is possible to map out possible Price Performance Ratios showing possible values associating different unit output price variations in response to input unit cost variations.

Figure 1

Price Performance Ratios (PPRs)

associated with different unit input value movements & movements in unit output prices

| Unit input costs | Unit output price change % |

| change % | -20 | -15 | -10 | -5 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 |

| 20 |

This area represents

the innovation

target zone | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 1.00 |

| 15 | 0.00 |

0.33 | 0.66 | 1.00 | |

| 10 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | | |

| 5 | 0.00 |

1.00 | | | |

| 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | | | | |

| -5 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 1.00 | | | | | |

| -10 | 0.50 | 0.66 | 1.00 | | | | | | |

| -15 | 0.75 | 1.00 | | | | | | | |

| -20 | 1.00 | | | | | | | | |

Innovation target zone | | Desirable states | | Undesirable states | |

|

PPR maps can be associated with different types of economic activity and sectors by over-laying actual PPRs over the PPR map. This can help identify sector innovative target zones. These are the zones of operation that can only be entered as a result of a quantitative improvement in corporate productivity. These maps can be used by corporate managers to identify optimized competitive growth strategies and tactics. The real ability to move a company's operations towards an innovation target zone, so as to become increasingly competitive, depends upon an assessment of the trade-off between investments in technology and human resources in response to changes in input costs (made up of fixed overheads as well as variable inputs), the price elasticities of consumption3 facing a product or service and selecting the prices providing the best consumption and income response to price-setting. Depending upon the state of factor, product and service markets, the achievement of higher productivity and margins depends upon a proactive reconfiguration of the key input factors.

Figure 2

Direction of travel to secure increasing performance and real incomes

Current PPRs indicate the direction of movement of a company's productivity in terms of their ability to moderate or lower unit output prices.

In macroeconomic terms the overall objective is to provide incentives for companies to opt for price moderation or reduction so as to:

- stabilize or increase currency purchasing power

- create a situation of a generalized rise in real incomes (combining currency stability with declining unit prices)

The Real Incomes Approach

Practice

Enough has been stated above to explain why the levels and distributions of real incomes provide an excellent indicator of the status of the economy. The rate of increase in real incomes provides a more realistic measure of growth. This is because real incomes are founded in price performance and the value of the currency. As far as consumers and the purchasers of capital equipment are concerned, changes in productivity are reflected in the unit prices they pay for specific qualities of goods and services. Note that this has no relationship to any centrally-imposed monopolistic interventions in markets by the state to fix interest rates or attempts to influence demand through taxation or government expenditure. Productivity and its impact on currency values relies upon decisions and actions that remain in the hands of corporate management so as to adjust values according to the ability of the company to optimize resource allocation to maximize income.

The direction of travelThere is general agreement that it is preferable to provide the freedom for social and economic constituents to decide on those actions best suited to their particular circumstances. The arbitrary absolutes of imposed rates of taxation and interest rate-fixing are inappropriate and disruptive. The most policy-makers can hope to do is provide incentives that have the effect of encouraging economic activities to take on a productive direction of travel. Preferably this direction of travel should benefit all, to a greater or lesser extent, as a direct outcome of their own decisions. Naturally to manage the direction of travel the microeconomic objectives must be the same as those desired for the economy as a whole so that business rules not only benefit individual companies but, through aggregation, the whole economy. Thus the beneficial direction of travel is that which improves the value of the currency through productivity increases. The direction of travel, as opposed to absolute measures as real incomes, have already been described in terms of the PPR maps (Figure 1 and 2). The direction of travel is associated with falling PPRs which signifies that unit output prices rise more slowly than unit input costs. Since the profit category has been eliminated from the accountancy categories the main interest is the maximization of incomes which will be related to corporate revenues. However, the growth in revenue will depend directly on the reaction of consumers to unit prices reductions.

Price elasticity of consumption (pEc)At any price level the growth in consumption of the production of any economic unit will depend upon unit prices. The lower unit prices fall the larger the volume of products and services consumed. Lowering of prices has an important impact with the consumption of the lower priced products and services rising and output from the lower-priced company beginning to substitute the output of companies with higher unit prices.

The percentage increase in consumption with a percentage reduction in unit prices is known as the price elasticity of consumption (pEc)

4. Price reduction generates what is known as an income effect in that a given nominal income can purchase more of a product or service because in fact real income has risen due to the unit price reduction.

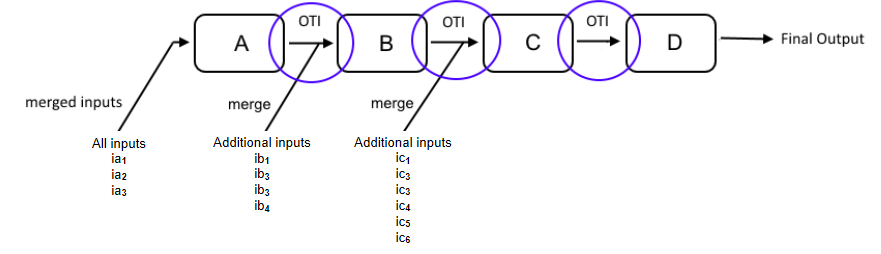

Supply chainsThe impact of price elasticity of consumption (pEc) is that is determines sales volumes at all points in a supply chain. The final demand for a product or service at the consumer or enterprise levels is a reflection of unit prices, product quality and income distribution.

Absolute and relative unit pricesBecause of the common practice of applying corrections for inflation by applying interest rates or inflation indices, track is lost of the fact that a strong distinction needs to be made between relative and absolute falls in prices. When there is a state of general price increases the company whose unit prices rise at a slower rate than others may gain from relative rises in consumption as a result of buyers substituting their products and services for those with higher prices. However, this does not have a real incomes effect, it only causes real incomes to depreciate at a slower rate. What is required is absolute unit price declines in order to generate a net positive gain in real incomes.

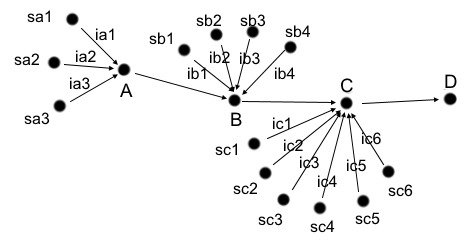

The nature of supply chainsFigures 1 and 2 show that in order to sustain or increase real incomes the price performance ratio (PPR) needs to be less than unity (1.00) or optimally less than zero (0). Currency depreciation or appreciation is generated in a cumulative form as a result of the nature of the transactions that take place in the supply chain. The required effect is for policy to encourage each company to maximize their income by minimizing their feasible unit output prices. This requires a logic that aims to optimize resources allocation to maximize feasible income in accord with the selection of unit prices that generate the best income in accord with the prevailing price elasticity of consumption.

Figure 3 shows a simple segment of a supply chain containing four producers, A, B, C and D. Supply chains are not usually simple linear relationships but when a company purchases an input from one company they will normally purchase other inputs from other companies to collect the components necessary for them to build whatever their processes produce for sale. The inputs are listed in the example of Figure 3. In the case of producer by A three inputs are used to produce their output (ia

1,ia

2, and ia

3) If we assume company A produces a single output or service then this is combined with an additional 4 inputs in the case of B (ib

1 etc.) and B's output is combined with six additional inputs in the case of C (ic

1 etc.). The outputs of the companies A, B and C undergo a transformation from being outputs from these companies into inputs to companies B, C and D. These supply chain segments where this transformation take place are indicated by the blue circles (OTI - Output Transformed to Input) Therefore a supply chain is more like a supply mesh with input sources fanning out around the purchasing companies. This concept is illustrated in Figure 4.

The importance of this structure to supply chains is that the significance of the impact of price variations of any single input is influenced by the unit prices of the additional inputs as well as their total value. Therefore in determining variations in unit costs there is a need to weight this calculation by the quantities and the unit prices of all inputs in order to determine the actual variation in unit costs.

Figure 3

A segment of a supply chain

|

Figure 4

A segment of a supply chain as a mesh made up of fans  |

Unit cost attenuationDepending of the number of inputs, their quantities and unit price variations, the impact of variation of any given input on total unit costs depends upon the weight of the value of that input in the components used. The general effect is that the price variation impact is attenuated or weakened. By way of example, for example in the case of company A, the impact of price variations on the input ia

1 is shown in Tables 5 and 6.

Table 5 The impact of a 50% rise in the unit price of ia1 is a unit cost rise of just 9.09%

| Period 1 | Period 2 |

| Input | Quantity | Unit price | Totals | Quantity | Unit Price | Totals |

| ia1 | 10 | 20 | 200 | 10 | 30 | 300 |

| ia2 | 20 | 30 | 600 | 20 | 30 | 600 |

| ia3 | 30 | 10 | 300 | 30 | 10 | 300 |

| Σian | | | 1,100 | | | 1,200 |

Table 6 The impact of a 50% fall in the unit price of ia1 is a unit cost fall of just - 9.09%

| Period 1 | Period 2 |

| Input | Quantity | Unit price | Totals | Quantity | Unit Price | Totals |

| ia1 | 10 | 20 | 200 | 10 | 10 | 100 |

| ia2 | 20 | 30 | 600 | 20 | 30 | 600 |

| ia3 | 30 | 10 | 300 | 30 | 10 | 300 |

| Σian | | | 1,100 | | | 1,000 |

A general conclusionUnit cost attenuation is a common characteristic of complex supply chains and the degree of attenuation tends to increase as progress is made down the supply chain. However, an additional issue associated with profit, and an important additional dimension of the profit paradox, is that by focusing on profit per se tends emphasize maintaining profits. This can reverse the advantages of attenuation in unit costs due to the relationship between unit prices and profits. Therefore, under generally inflationary conditions, there is no incentive to moderate prices when unit costs rise otherwise unit profits will fall. Therefore the function of policy needs to be to provide a positive incentive for companies to moderate unit prices. Therefore policy needs to encourage a general unit price response to variations in unit costs that attenuates unit prices or moderates them when unit costs rise and helps reduce them when unit costs fall.

Policy incentiveIn order to encourage management to make decisions on resource allocation optimization to secure unit price moderation or reduction there is a need to provide a positive economic incentive. Under the profit motive moderating unit prices in the face of rising unit costs lower unit margins and raises risks. However, the elimination of this motivation by substituting profits by investments in technology and human resources and substituting the profit motive by a real incomes motive can reduce these constraints and reduce risk on the basis of the identification of optimized resource allocations. Thus an incentive that lowers the risk of unit price reductions can help companies gain market penetration and increased income. This would secure simultaneously the microeconomic and macroeconomic objectives of enhanced real incomes both of those who own and are employed by companies as well as their customers.

The degree to which a company achieves price moderation can be measured by the price performance ratio (PPR). The PPR value achieved by any economic unit is established directly by management decisions and actions. Rather than bear down on companies with centrally-established rate for interest and taxation these instruments can be substituted by a positive productivity incentive in the form of a Price Performance Levy (PPL). This can be applied by selecting from a very large range of optional formulae. By way of example a power function can be used where the main variable that determines the value of the Levy is the PPR. Thus the PPL can be of the following form:

PPL=L(PPR)2 . . . . . (1)

Where:

PPL is the levy applied to the company

L is the base rate Levy,

PPR is the price performance ratio.

Assuming a base rate Levy of 20%, Table 7 shows the range of values of the PPL according to the PPR achieved by a company.

Table 7

Price Performance Levies associated with different Price Performance Ratios

| PPR | Base rate Levy | PPL | Bonus |

| l.00 | 20% | 20.00% | 0.00% |

| 0.75 | 20% | 11.25% | 8.75% |

| 0.50 | 20% | 5.00% | 15.00% |

| 0.25 | 20% | 0.63% | 19.37% |

| 0.00 | 20% | 0.00% | 20.00% |

As can be seen under a fixed policy-related base rate Levy of 20%, management can allocate resources so as to come up with the PPR they desire and thereby pay a Levy varying from 20% to zero. Naturally managers will try and avoid paying the Levy and the only way to do this is lower their PPR by improving demonstrable productivity. Companies can easily manage their PPR values by carrying out incremental investments in technology and human resources which will raise unit costs in addition to any rises associated with purchased unit input variables. However, the resulting gains in efficiency must be recorded in the form of moderated unit output prices. In other words the benefit to the economy becomes real and demonstrable. The amount of PPL avoided that is based on increased productivity and sales is a bonus category described below.

The Price Performance Levy does not contribute to government revenue

The PPL is not designed to raise government revenue but it is only an incentive mechanism. It is proposed that government revenue should be raised from personal income tax in a framework where the majority of the workforce are paid enough to afford to pay tax. Thus conventional corporate taxation would be replaced by a requirement to pay a living wage plus some margin that would be paid in income tax by employees.

Income generation and bonusesHigher shareholder and employee incomes can only rise as corporate productivity and revenues rise. Increasing revenues are a direct outcome of the correct price-setting and the price elasticity of consumption securing a growth through market penetration. The revenue streams will be divided into the following accountancy categories:

- Corporate revenue from sales

- Income of individuals associated with the company

- Current operational costs

- Cash

- Assets

- Investment in technology

- Investment in human resources

The PPL is applied to the margin between corporate revenues and the sum of operational costs and shareholder and employee basic incomes. Therefore before this margin is divided into cash, assets and investment in technology or human resources it is subject to the PPL. Clearly a low PPR will result in a larger net margin. The investments in technology and human resources can be used to raise operational costs by allocating investment values as overheads to operational costs thereby facilitating the reduction in the PPR while raising productivity. However, in order to benefit from the PPL manipulation productivity must be expressed in the form of price moderation and a low PPR. This is to avoid "pro-forma" paper-based reporting as a means to lower the PPL.

Shareholder incomes will vary with overall performance so that any bonus arising from higher revenues (see Table 7) will be proportional to the size of share holdings. Where shareholders work as executives and managers these positions will be subject to a standard professional scale of salaries

5. Employees will also be paid on the basis of a standard scale of salaries that relate pay to qualifications, experience and capabilities. Bonuses would be distributed pro rata against shareholding and scales of personnel income. As a result customer will benefit from moderated price or reduced prices and personnel will gain immediately from higher incomes paid in compensation for productivity increases, expressed in the form of competitive unit prices and market penetration.

Efficiency & effectiveness The ability to sustain the process of increasingly effective pricing is dependent on current operational efficiency and organizational effectiveness and future productivity. This is an evolving state of affairs that can only be sustained through a constant and careful adjustment in the combination of technology and human resources. The human element is important where attention to detail and experience in operations advances useful information (explicit knowledge) as well as personal development of capabilities in the application of techniques (skill) which comes only with direct exposure and practice in the application of the techniques concerned (tacit knowledge) (See:

Tacit & explicit knowledge). In the United Kingdom, tacit knowledge is a largely marginalized resource in resource allocation decisions. However, tacit knowledge is one of the resources that is guaranteed to contribute to productivity levels on a constantly evolving basis. The beneficial impacts of tacit knowledge that has accumulated with experience has been analyzed and described in the form of the so-called learning curve

6. One of the earliest measurements of the contribution of the learning curve to productivity was established on the basis of empirical evidence by Wright and published as far back as 1936

7. The state of the art application of learning curve theory is based upon computer algorithms has been described by Belkaoui

8. The contribution of tacit knowledge to productivity and the measurement of the impact of tacit knowledge, that is, embedded capabilities of human resources represents a large void in microeconomic theory although there are algorithms that can be used to determine and project the precise impact of the learning curve on productivity

9. Such procedures are an important and commonly over-looked resource for corporate planning.

Operational practiceA quantification of the roles of explicit and tacit knowledge, combined with feedback from customers and market dynamics, helps provide a clear perspective on an investment hierarchy that can identify those actions with the highest return and production options based on low cost pathways. These involve modifications in existing production configurations, updating with state-of-the-art technology as well as in-house innovation based on trade-off analysis between gains to be achieved through different technical and human resource techniques. Such decisions can help improve productivity and real incomes through a sustained creative, as opposed to destructive, transformation

10.

Decision-support mechanismsThe Real Incomes Approach enables the full range of existing mathematical, logical, operations research methods and procedures have a more potent impact enabling more productive optimizations by having managers operate in an environment where policy-induced constraints such as the profit paradox and government revenue-seeking have been removed from the decision analysis models. There is no longer any need to attempt to minimize "profit" to avoid taxation and no incentive to reduce wages to protect "profits. The removal of such constraints creates a transparent basis for the operation of business rules supported by practical incentives that aim to maximize feasible real incomes. Indeed, companies are left free to maximize their incomes and bonuses based on a decision analysis environment involving lower risk.

Unit price attenuationThe natural unit costs attenuation that occurs in a supply chain has been described above. The impact of Price Performance Policy is to accentuate the attenuation in unit output prices on a similar basis while increasing real incomes. In an inflationary state the PPR is given by:

PPR = ΔUp/ΔUcTherefore the inflation generated by an economic unit is given by:

PPR(ΔUc) = ΔUp

In a supply chain part of a downstream company's inputs are made up of the outputs of companies located upstream. Thus the cumulative outcome in terms of inflation is as follows in the case of a 3 stage supply chain:

PPRc(PPRb(PPRa(ΔUc0)))Thus if the average PPR is 1.00 an input inflation ΔUc

0 of say 10% will translate into an output inflation of 10%. If the average PPR is 0.5 the 10% inflation will translate into an output inflation of 1.25% and if the PPR average is 0.25 then the output inflation will be 0.156%. The reduction in unit output price rises will, depending upon the price elasticities of consumption, result in a rise in consumption for the companies with relatively lower unit prices. The more competitive companies will have increased bonuses leading to an improvement in the real incomes of those associated with the economic unit as well as their customers.

Dispelling some mythsI hope these explanations are sufficient for the reader to realize that conventional theories based on the aggregate demand model (ADM), that is Keynesianism, monetarism and supply side economics all assume that inflation is the result of increases in "demand". Indeed, all of these macroeconomic policies rely heavily on this logic in establishing objectives for policies. However, the governor of inflation or deflation is not demand or lack of it but rather the governor is the price performance ratio which is controlled by corporate management decisions. As we have observed management decisions result in misallocations under the influence of the profit paradox and inappropriate frameworks for government revenue-seeking. By eliminating these constraints inflation or deflation become more directly related to productivity expressed in terms of the PPR and unit output prices arising from better resource allocation at the corporate level. Under Price Performance Policy the most significant outcome is that inflation is controlled and income distribution ensures a rise in real incomes through the impact on the stability of the purchasing power of the currency.

1 Hector McNeill is director of SEEL-Systems Engineering Economics Lab.

2 Peter Drucker (1909–2005) - was an Austrian born American business management consultant.

3 Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950) - was an Austrian born American political economist.

4 pEc-Price elasticity of consumption is similar to price elasticity of demand but the sense is geared towards supply side logic and the PAC (Production Accessibility Consumption) Model of the economy as opposed to the ADM (Aggregate Demand Model). See

"The PAC Model of the economy"

5 Standard salaries: these are pre-determined minimum salaries and wages paid for different grades of work with adjustments for experience and qualifications. These are normally set out in "professional scales". Minimum salaries and living wages can be included in these scales as well as scales for managers who are also owners or shareholders. In the case of shareholders the classifiction would not be salaries but would consist of payments made in proportion to shareholding and declared dividends net of the PPL.

6 The learning curve: A well-established quantitative relationship between a person's experience in applying a repetitive task and their evolving competence mesasured in terms of speed, accuracy and yield, including output quality.

7 Wright, T. P.,

"Factors Affecting the Cost of Airplanes", Journal of Aeronautical Sciences, (Vol. 3, No. 2) 1936.

8 Belkaoui, A.,

"The Learning Curve - A Management Accounting Tool", Quorum Books, 1986.

9 Measurement of learning curve impacts: Seel-Telesis adaptive learning tool, SEEL, 2000.

10 Destructive transformation: was a term used by Joseph Schumpeter to describe the process of innovation. However, since the process evolves from accumulated knowledge and represents an improvement on current practice preference is given to the term creative transformation.

All content on this site is subject to Copyright

All copyright is held by © Hector Wetherell McNeill (1975-2015) unless otherwise indicated